photo courtesy of Cindy Mosqueda, loteriachicana.net

If you can make it to only one restaurant on your first trip to Tijuana, that one may as well be La Cantina de los Remedios. It offers a quintessential Mexican experience that can serve as the keystone to understanding all the culinary arts of Baja. The menu is Mexican comfort food, the inspiration for all our alta-cocina/Baja-Med pretensions; the setting, reminiscent of the good old days, includes sly references to the Tijuana of half a century ago.

Because the nostalgic details are historically accurate, and because the menu is strictly legit (no combination plates even though they do serve tacos, enchiladas, and tostadas), the place attracts a lot of locals out for a good time. It's also gringo-friendly – you can get both waiters and menus in English and they accept all major credit cards.

Their menu is varied enough to allow customers to share a snack over drinks, to eat a full meal, or to throw a small party. They offer more than a dozen botanas, four salads, a pasta, five soups, and three tortas. The main dishes include about a dozen forms of chicken, half a dozen shrimp and two fish fillets. Choices of grass-fed beef are extensive, including four parrilladas (mixed grills), arrachera, tampiqueña, a few filets, and a couple U.S.-style steaks. The desserts include favorites from both sides of the border such as crepas de cajeta, flan, carrot cake, and guava cheesecake. And they make one of the best margaritas in the business.

Few restaurants understand their customer base as clearly as does Los Remedios. It has flourished for more than a quarter-century by focusing on the authenticity of its product while continually adapting to the changing mix of tourist and local, first-timer and regular.

Built to look like a hacienda in Jalisco and named Guadalajara Grill, it was one of the first businesses to go up the Zona Río. In those days its style was boisterous and irreverent. The décor might have been the work of Diego Rivera on acid. The waiters announced the first course by saying “here’s today’s soup … and yesterday’s bread”. Gentlemen were actively discouraged from wearing ties. (The customer would have it cut off him, the trophy tacked onto a wall with a hundred others. The locals were in on the joke and used it as an opportunity to get rid of ties they didn’t like but the ritual was abandoned when the head of a Japanese maquiladora, having lost a favorite tie to the wall, took umbrage.) The place offered the ideal party atmosphere for the 1980s.

Then the economy became somber. Customers, wishing their pesos would go farther, started feeling nostalgic for happier times. As the new millennium came in, the restaurant responded by redesigning itself.

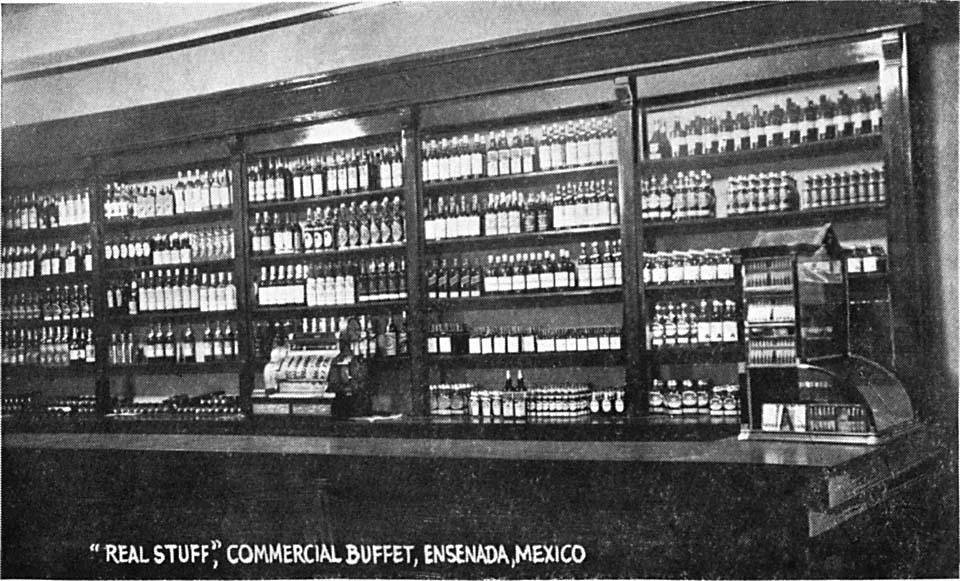

The Chupacabras with the blinking red eyes came down: in its place is a long-gone Tijuana. One side of the dining room evokes our Cine Zaragoza during the Golden Age; another, the bullring that used to stand on Agua Caliente Boulevard. The bar copies the Hotel Comercial’s, from the 1920s, while the slogans painted along its runner – “pida su cubilete”, “pida su dominó” – invite you to make use of table games that were popular in the upscale bars well into the ’50s and ’60s. The sassiness previously offered by the waiters has receded into witticisms painted on the crossbeams – “If you drink to forget,” says one, “please pay first.”

The cantinas of Mexico’s Golden Age often had playful names. Customers were coaxed in with promising imagery – Salsipuedes (“Leave If You Can”), El Tocador de Afrodita (“Aphrodite’s Dressing Table”), Los Eructos de Una Dama (“Milady’s Belches”), El Coloquio de los Megaterios (“A Symposium for Giant Sloths”), Los Hombres Sabios Sin Estudio (“The Wise Drop-Outs”) – or they were provided an excuse for when the wife demands to know where they had been – La Parroquia (“Church”), Aquí Nomás (“Right Here”), Contigo hasta la Muerte (“With You Forever”).

The restaurant’s name follows this tradition of playfulness. On one hand, it invokes La Virgen de los Remedios, one of Mexico’s patron saints. On the other, because remedios can mean “medicine”, the name alludes to the curative power of tequila and to the famous proverb para todo mal, mezcal; para todo bien, también (“drink mezcal for everything that ails you as well as what’s good for you”). Even so, the new name emphasizes their bar at the expense of their food, so, most recently, the company has started to downplay the full name in favor of simply “Los Remedios”.

Behind the scenes, the kitchen was also redesigned. It’s now a showpiece of ergonomic efficiency, which makes the cooks happy and allows the restaurant to remain competitive. Even the breads and table salsas are produced in-house while the tortillas, which require specialized machinery, are supplied under contract according to the restaurant’s proprietary recipe. The chef gets to exercise his creativity with the special menus each month that highlight a cuisine from one of Mexico’s colonial regions or from another Hispanic country.

The restaurant’s customers have been looking for value now more than ever. In response, there are four special deals to attract them. (1) The famous prix fixe, “menú todo incluido”, is available every afternoon. This is a four-course meal (appetizer, soup or salad, main course, and dessert, all chosen from the à la carte menu) plus unlimited drinks for about twenty-six dollars. (2) Los Remedios also offer an extended happy hour in the evenings, from 6:00pm to 10:00pm. This gives the customer access to their entire bar, even the super-premiums, at two-for-one pricing. There are some very fine tequilas and Cuban rums among those super-premiums. (3) The Kilo is the most recent special offer. It has become extremely popular with the local crowd because it’s a perfect way to turn a tableful of people into an instant party – more than two pounds of meat and a bottle of liquor with mixers (or a lot of beer) for one low price – and no worries about separate checks. (4) The VIP program, “Socio Los Remedios”, rewards diners by crediting a portion of each check into a special account that the customer uses by means of a private debit card. This represents an additional saving of ten percent or better on repeat business. The waiters will explain the details.

Our readers have been provided with their own special deal. Download this discount coupon for 10% off the à la carte menu and present it to your waiter when you place your order. One coupon per person, please.

Various musicians drop by on Friday evenings and Saturdays beginning in the late afternoon, usually a norteño, mariachi, or jarocho group or a trio romántico. Open daily from 1:00pm to midnight; to 10:00pm on Sundays. Paseo de los Héroes at the Lincoln glorieta (see our Points of Interest map). Valet parking. One block west of the City Tour stop at Hotel Lucerna; a taxi from the border should cost between three and five dollars.

0 comments:

Post a Comment