• • • SEE UPDATED INFORMATION AT END OF ARTICLE • • •

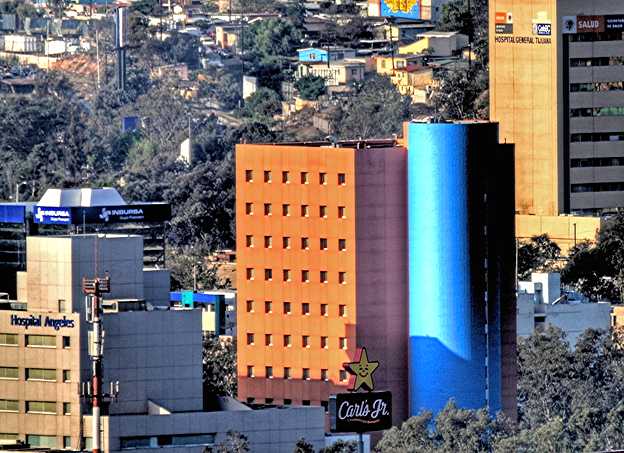

Crossing the border on 4 July 1920

Perhaps the most annoying aspect of crossing the U.S.–Mexican border is the unpredictabiity of the Customs lines. Sometimes five minutes, sometimes five hours, sometimes caused foreseeably, sometimes capriciously. To anticipate this difficulty, every “frequent crosser” has their favorite source of border-wait information.

Decades ago, the local radio stations began sending spotters to the San Ysidro border to phone in their

Reporte de la Garita every half-hour. Channel 12 and Síntesis television now issue reports on the hour and half-hour during their news programs. When the webcam craze hit, Telnor (the local telephone company) began offering real-time images of the four major sources of vehicular traffic at the point where they converge, later adding a fifth webcam for Otay’s non-commercial lanes. Recorded information is available by telephone (San Ysidro Port of Entry, +1-619-690-8999; Otay Mesa, +1-619-671-8999; Telnor’s service, +52-664-700-7000; from Mexican cell phones, *LINEA). Most popular recently are various Internet portals, primarily tourist sites and Tijuana newspapers, that embed the U.S. government’s reports and the Telnor webcam feeds.

A programmer here in Tijuana known by the

nom de guerre “IsReal” has come up with yet another way to get border-wait information: it can now be integrated into your web-browser.

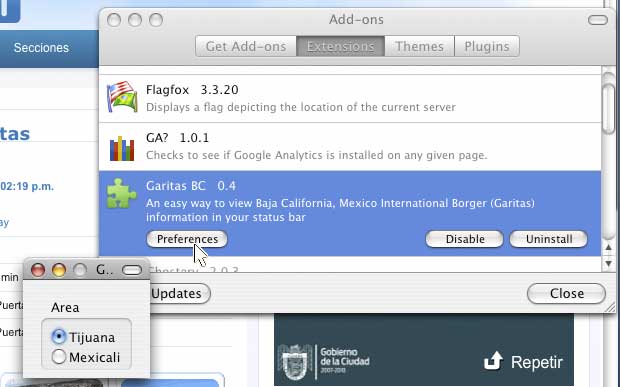

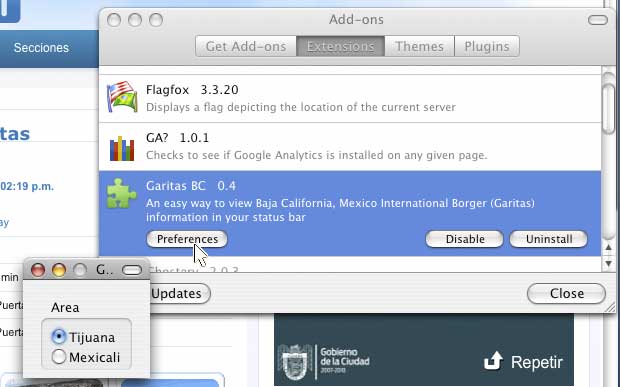

GaritasBC is an extension for Firefox that sits unobtrusively in the right-hand corner of your status bar. When you roll your cursor over it, a tooltip window pops up containing the most current reports for Tijuana and Tecate; right-click to select from a menu of Telnor webcams. The current version of the extension also allows you to access the same information for the Mexicali crossing.

click to enlarge

GaritasBC currently reports all northbound wait times, in Spanish. The source of this information is U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which currently updates its data at the top of every hour. The GaritasBC extension checks for new data every ten minutes, however, so its reports are as timely as the CBP affords.

The extension can be

installed automatically by downloading it while running Firefox.

Once installed, the name “GaritasBC” will appear in the status bar at the bottom-right corner of your monitor. Place your cursor over the name and the current report will appear at the tip of your cursor. Right-click (or control-click) on the name and a pop-up menu will offer the available webcams; selecting one will replace whatever is in the active window of your browser with the current static image from that webcam.

To switch between Tijuana/Tecate and Mexicali reports, chose the appropriate radio button in the extension’s preference: from the Firefox menubar -> Tools -> Add-ons -> Extensions -> GaritasBC -> Preferences.

click to enlarge

IsReal describes the development of GaritasBC as a labor of love – in other words, it is not being promoted commercially. Consequently, Firefox continues to classify it as beta software (primarily because of its austere interface and because it’s still waiting to be reviewed by the Firefox editorial team) even though it is now in its fifth version and has received no reports of bugs or instability. If the extension generates enough interest, IsReal has plans to get it out of beta by giving it more a of a graphical interface and by including reports for all the U.S. terrestrial ports of entry along the Mexican border.

Updated August 2018The world now uses mobile apps, so this Firefox add-on has not been updated and is not compatible with current versions of the browser.

There are now about two dozen of such smartphone apps to choose from … and all of them show a lot of user dissatisfaction due to inaccurate wait times.

We need to be clear at this point: GaritasBC – as well as the smartphone apps that have replaced it – all suffer from a significant defect in that they’re little more than different “skins” for displaying Customs and Border Protection’s RSS feed.

Official CBP procedure has each Port of Entry along both land borders sending to Washington DC before the top of each hour what it estimates its wait-times are. Washington then makes the basic information available to the general public on its

Border Wait Times webpage. These wait times are concerned with travelers coming into the US only. We know of no reports available for the traffic entering Tijuana.

When you check users’ reviews of the currently available apps, you’ll see a lot of anger over the inaccurate times but not over the apps themselves. As far as Tijuana goes, at least, the CBP has been wildly dishonest in its reporting of these numbers. Some of the inaccuracy is inherent in the CBP’s methodology: the data are sent to Washington only once every hour and, if that transmission arrives late, those data won’t be reported by CBP until the top of the following hour. Whenver the hamsters turning the treadmill that powers the CBP system get tired, the website continues to report the last transmission it received until the hamsters start working again.

Another reason for the inaccuracy – at least according to local lore going back several generations – is due to

tortuguismo, that is, a tacit governmental policy of impeding travelers so as to make the idea of avoiding Tijuana and staying in the US more attractive. Motorists often comment that it takes them just as long to clear Customs regardless of whether there are three cars or thirty cars in front of them. Pedestrians have even stranger stories to tell.

To counter the unreliability of the official information, there have already been several attempts to harvest real-time data. One pioneering effort in this direction, bordertraffic.com, has been trying to monetize the existing CCTV traffic feeds: this might make sense for those who cross the border frequently and who are willing to learn how to interpret the video information. UCSD’s experimental app, “Border Wait Times”, attempted to crowdsource the wait times by means of its users’ GPS pings – excellent methodology – but its web server, traffic.calit2.net, was taken offline by the university without explanation. Other attempts at crowdsourced data, such as

Garita Center, still need to attract a crowd.